Written by: David Stonehouse | AGF

For much of the past two years, investors have been fixated on the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed). After March 2022, when it began raising interest rates for the first time in four years, the big questions became “How high would rates go?” and “When would the Fed stop?” Now, as we approach a new year and the rate-hiking cycle seems to have paused, the question has shifted to “When will the Fed start cutting?” Certainly, these questions matter. As it leads the global monetary policy charge to contain inflation, the central bank of the world’s largest economy can have a substantial impact on both global equity and fixed income markets. Yet, as important as the Fed undoubtedly is, investors may potentially benefit from paying more attention to another public institution as they look forward into 2024: the U.S. Department of the Treasury.

It doesn’t attract all the headlines the Fed does, but the Treasury plays a vital role in the U.S. financial system and in interest rate dynamics. Basically, it is the financial arm of the U.S. government, and one of its jobs is managing America’s federal debt instruments. When Washington wants to spend more money than it gets in revenue (from taxes, largely), the Treasury issues debt in the form of marketable securities such as bonds and Treasury bills. These bonds pay interest set by the Treasury as the coupon, but their yield is determined by supply and demand. If demand is high and/or supply is low, yield goes down; if demand is low and/or supply is high, yield goes up. And it’s here, in the supply-and-demand world of Treasuries, that some very interesting, and perhaps unsettling, dynamics are playing out.

For one thing, the U.S. Treasury has been very busy lately, because the federal government has been spending money and running deficits. Big deficits. Government borrowing spiked during the COVID-19 pandemic and has just kept on growing since then. In fact, over the past 10 years, the U.S. federal debt has nearly doubled, reaching US$33.4 trillion as of mid-November, up from US$17.2 trillion in 2013.

"It doesn’t attract all the headlines the Fed does, but the Treasury plays a vital role in the U.S. financial system and in interest rate dynamics."

Meanwhile, the federal deficit as a percentage of U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) will grow from 5.4% in fiscal 2022 to 6.3% in fiscal 2023, marking the first increase in deficit/GDP since the pandemic year of 2020. And it could keep growing. The Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) perhaps conservative forecast from June 2023 has the federal deficit rising steadily over the next several decades, hitting 8% of GDP by 2053. The deficits in 2024 and 2025 are projected to be in the range of US$2 trillion each year.

Does it matter? Proponents of Modern Monetary Theory, or MMT, would claim that it does not – that governments can always just print more money. But it is difficult to ignore the probable costs of such continued fiscal laxity. True, a U.S. government default seems like a remote possibility, notwithstanding regular congressional debates over the debt ceiling. Yet running ever-higher deficits means that the Treasury must issue more and more bonds. The increased supply puts upward pressure on yields, which, along with those swollen deficits, will likely mean the government will pay more and more in interest. According to the CBO, interest payments comprised about 10% of overall federal spending in 2023; they are forecast to rise to nearly 15% by 2033 and 23% by 2053. To make those payments, the government may have to issue even more bonds, putting further upward pressure on yields.

Of course, the U.S. government could do something about the deficit crunch: cut spending and/or raise taxes. Yet successive administrations and Congresses, Democratic and Republican, have shown little commitment to either approach. And if, as some observers still think is likely, the U.S. economy plunges into recession in 2024, then we believe the political pressure to increase spending and keep taxes low will probably be acute – especially in an election year.

"Foreign holdings as a share of all U.S. public debt have declined generally over the past decade and the net sellers include Japan and China."

As a consequence, we believe the elevated supply of federal bonds may contribute to yields being higher than they otherwise would be based solely on the underlying economic fundamentals. This situation is exacerbated by the fact that governments in other parts of the world are also running deficits, contributing further to the supply of sovereign bonds.

There are, however, dynamics at play on the demand side, too – namely, some traditional buyers of U.S. debt are rethinking their commitment to Treasuries.

In recent years, foreign buyers have been paring their holdings of U.S. government bonds. Foreign holdings as a share of all U.S. public debt have declined generally over the past decade, and the net sellers include Japan and China – the two largest foreign holders of Treasury securities. Japan is starting to normalize interest rates, but at a very gradual pace, and its still-low interest rates have required it to defend the yen, which has resulted in periodic selling of U.S. Treasuries. Between September 2022 and September 2023, Japan lowered its holdings of U.S. debt by 2.5%. The more dramatic reduction has been from China, which trimmed its U.S. Treasury holdings by US$123 billion over the same period – a reduction of nearly 14%. Several factors are at play, including geopolitical tensions and a desire to establish the renminbi as a reserve currency to rival the U.S. dollar and the euro.

Meanwhile, other significant buyers of Treasuries might not be so active going forward. U.S. banks must hold a certain amount of government securities to meet their reserve requirements, but they have been cutting their holdings recently, and will likely only need to increase holdings gradually in the coming years to meet their regulatory capital hurdles. And the “big daddy” of bond buyers from 2008 through the pandemic – the Federal Reserve – has of course switched to quantitative tightening. From June 2022 to mid-November this year, the Fed reduced its Treasury holdings by nearly US $1 trillion, which has not only removed a major source of demand but has actually added further to supply and contributed to the rise in yields.

This all leads to an important question: If China, Japan and the Fed are net sellers of Treasuries, who is going to buy them? One answer is financial institutions like insurance companies, which cover their liabilities by holding long-term debt and stand to benefit from higher yields. There’s another natural buyer pool, too, and it’s massive: investors, including pension funds, institutions and individuals.

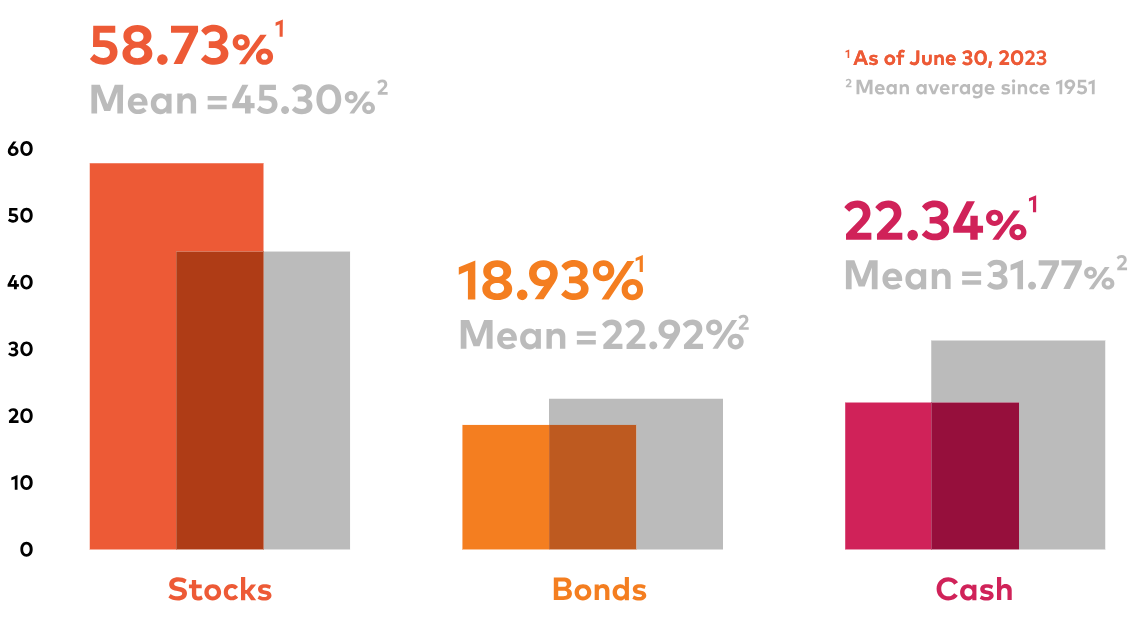

One might assume that the aggregate of investors could never rival the bond-purchasing power of foreign governments and the Fed, but in fact, investors have historically been the largest lenders of choice to the U.S. government. Interestingly, the pool of household capital encompassing retail, institutional and pension investors has been overweight in equities and materially underweight in bonds in recent years, which is perhaps not surprising given fixed income’s terrible performance over the past three years. Yet to shy away from bonds now may be to ignore the fact that for the first time in nearly 20 years, yields – even for “risk-free” Treasuries – have returned to historic norms, which represent far more attractive levels. There are signs investors already realize that. For instance, a November survey by Bank of America suggests that fund managers are turning more bullish on bonds than at any time since 2009.

U.S. Household Asset Allocation

Source: Ned Davis Research, June 2023. Chart shows quarterly data from December 31, 1951 to June 30, 2023.

To be clear, other countries around the world also face similar issues as government spending swells across the developed world, but it’s not quite to the same degree as in the U.S. where the outlook for debt, deficits and the bond market appears to be the gravest of all. Too many bonds and too few buyers rarely makes for a good outcome. But there is a less dire possibility, and it’s a strong one: namely, that where Japan, China and the Fed step away from Treasuries, investors will step up. In the end, the supply-demand dynamics that are so challenging to the U.S. government’s balance sheet and driving up interest rates might actually work to investors’ benefit – at least for those who are willing to set aside recent history and turn back to bonds.

Ultimately there is a clearing price (yield) for markets like U.S. Treasuries. While economic variables will have a significant influence on this level, it is also true that once yields rise to a sufficiently enticing level, they will attract enough buying interest from investors to take up the supply. One of the keys for capital markets in 2024 will be what those levels might be.

Related: Investors Urged To Be Vigilant to Possibility of Surging Oil Prices