Written by: Adam Schrier | New York Life Investments

Many strategists and experts have been wrong about rates, both fed funds and U.S. Treasury yields. This is why it’s important to be well diversified in fixed income — with so many different potential outcomes, a portfolio positioned seeking one specific outcome could be costly if that bet is wrong. For example, selling credit in 2022 to buy long duration has cost some investors hundreds of basis points.

Another bet we are seeing — advisors are holding large amounts of cash on the sidelines. With the three-month Treasury currently yielding close to 5.5%, most portfolios should have some cash. However, it may be advantageous to start shifting some of that cash into longer-duration bonds. And advisors know this — they know at some point they will need to get into the game, but many are waiting for the perfect time. Of course, timing markets is notoriously difficult, but in this case, they don’t need to be timed perfectly. In fact, we found that historically, being early has been better than being late during this part of the cycle.

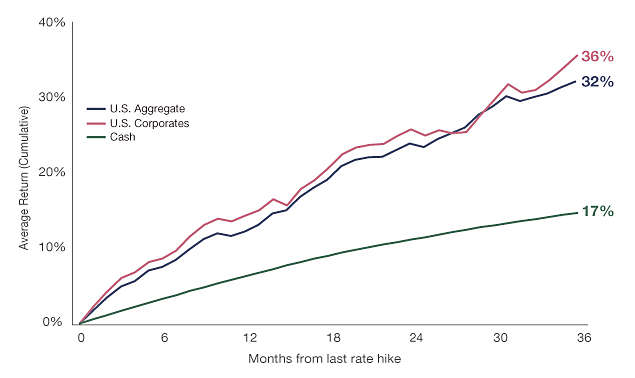

Being Early Has Been Better Than Being Late

We looked back at the past six rate-hiking cycles and calculated the average three-year returns of cash, core bonds, and investment-grade corporate bonds following the last rate hike. Corporate bonds outperformed core bonds, and both massively outperformed cash.

Source: FactSet, three-year performance start dates: 8/31/84, 5/31/89, 2/28/95, 5/31/00, 6/30/06, 12/31/18. Agg is the Bloomberg Aggregate Bond Index. Corporates are represented by the Bloomberg US Corporate Investment Grade Index. Cash represented by the ICE BofA US 3M Treasury Bill Index. Past performance is no guarantee of future results, which will vary. It is not possible to invest directly in an index.

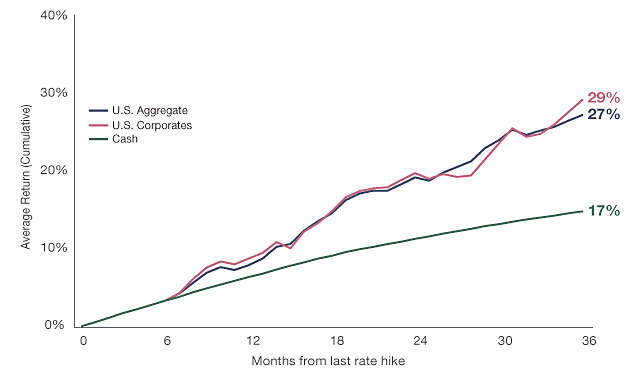

We then wanted to answer the question — “What is the cost of being late?” We looked at the same three-year periods and calculated the returns using cash for the first six months. For example, the corporate return is the average return for the six hiking cycles, staying in cash for six months following the last rate hike, and then invested in investment-grade corporate bonds for the subsequent 30 months. By waiting just six months, returns were down an average of 700 basis points (bps) over the three-year periods.

Source: FactSet, three-year performance start dates: 8/31/84, 5/31/89, 2/28/95, 5/31/00, 6/30/06, 12/31/18. Agg is the Bloomberg Aggregate Bond Index. Corporates are represented by the Bloomberg US Corporate Investment Grade Index. Cash represented by the ICE BofA US 3M Treasury Bill Index. Past performance is no guarantee of future results, which will vary. It is not possible to invest directly in an index.

Reinvestment Risk

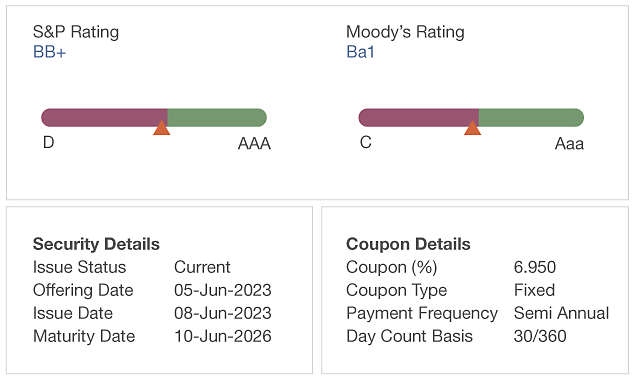

Another objection we often hear is that bonds don’t offer enough incremental yield relative to the risk-free rate to compensate for credit risk. However, we believe this logic is flawed, and here’s why:

Source: FactSet

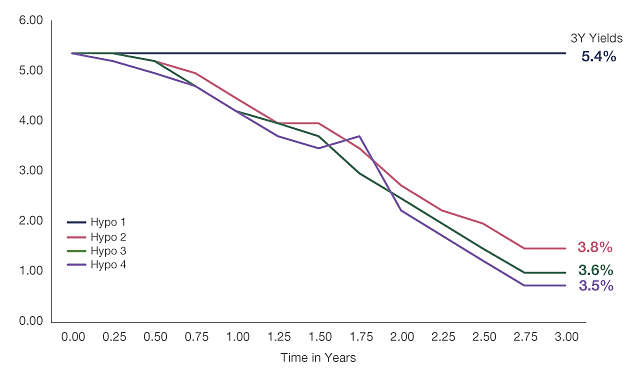

The example above is a high-yield issuer in the autos sector rated BB+, or one notch away from investment grade. It recently issued a three-year bond with a 6.95% coupon. If bought at par, its yield to maturity (YTM) is 6.95%, meaning if held to maturity, an investor would realize an annualized return of 6.95% for three years. One could argue, “That sounds good, but I can earn 5.4% with a three-month Treasury.” Is that true? That would mean that the three-month treasury would remain at its current level for the next three years. In our view, it’s more likely that the yield will fall, which exposes an investor to reinvestment or roll risk.

The chart above shows four hypothetical rate paths for the three-month Treasury yield, with the first one being a constant yield over the three-year period. The yields on the right reflect the equivalent three-year yield to maturity that would be realized for those rate paths. The important takeaway is that locking in attractive yields in bonds may generate even greater relative returns than is suggested by comparing a bond’s yield to that of short-term investments.

Outperforming a Bond’s Yield

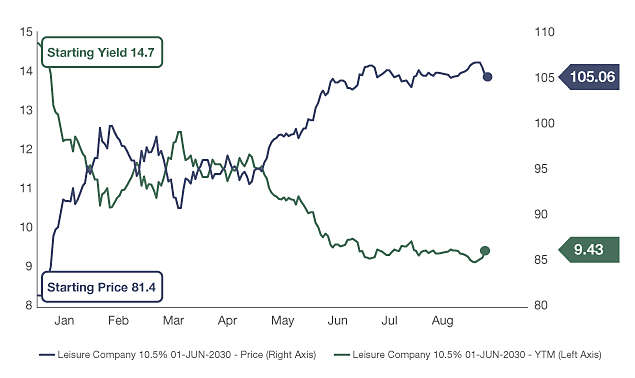

Additionally, it is possible for bond yields to decline, leading to bond returns that exceed their yield to maturities. For example, the leisure company shown below started the year with a 14.7% Yield to Maturity, meaning the bond’s theoretical annualized return from January 1 until the bond’s maturity in 2030 would be 14.7%. This YTM assumes that the bond price will appreciate from 81.4 to 100 at maturity. However, what actually occurred was this: its yield dropped sharply as its price increased to 105 in a matter of months, resulting in a YTD return of close to 40% as of August 31. At that point, bond portfolio managers could make the determination regarding its prospects and relative value, but this illustrates how discounted bond prices can lead to returns that outpace their yield.

Returns > YTM

Source: FactSet, ICE Index Platform, 9/7/23.

With aggressive Fed hikes and Treasury yields at levels not seen in years, there are plenty of places to turn for income. Many investors have stockpiled cash because, for the first time in over a decade, cash and short-term investments can earn a competitive yield. However, we found that investment-grade bonds have dramatically outperformed cash over three-year holding periods subsequent to a pause in rate hikes. Historically there has been a penalty for being late to moving out of cash, so it may be better to be early than late. Additionally, longer-duration bonds can lock in a yield to maturity, whereas the realized return of short-term cash investments have the potential to underperform starting yields due to reinvestment risk. Having a cash allocation in a portfolio makes a lot of sense in the current environment, but it may be beneficial for investors to start shifting some of that cash into bond portfolios.

Related: Why Financial Advisory Firms With Growth Ambitions Need Strategic Planning