You’re “Too Early” Cat Berman was getting a good vibe.

The CEO of CNote, a Bay Area startup fintech firm focused on socially responsible investing, explained, “We had an investor say, ‘This is phenomenal. Excellent team’.” Things were looking positive for this early stage company.

Then the investor added, “We’re just not sure if you’re too early because of your traction.” Berman dug deeper to understand what “too early” and “because of your traction” actually meant. She ultimately concluded he was basing the lack of “traction” on the fact that CNote’s fintech peers had raised ten times the amount of funds CNote had at the time. With this clarified, Berman was able to demonstrate that the fintech firms CNote was being compared to were 1) in a different market space and 2) demonstrating the same market penetration as CNote. In other words, CNote had done more with less.

Every industry or professional sector has jargon that members within the group use to cut through some of the complexities of communication. But the downside of jargon is that it can be meaningless to outsiders or worse, it can unintentionally (or intentionally) exclude those trying to interact with the group. Minorities and women entrepreneurs attempting to finance their business ventures are frequent casualties of a specialized lexicon from investors and lenders, some well-meaning, that indicates a lack of trust or support.

The Financial Case for Minority- and Women-Owned Business Enterprises

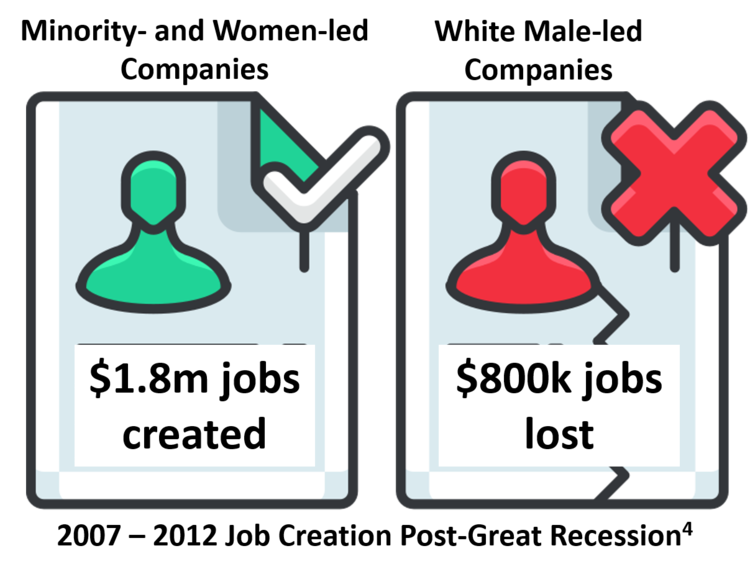

Entrepreneurship is an important driver of the US economy and is deeply rooted in its history of pioneers, innovators and risk-takers. Despite the US’s dependence on entrepreneurship to create jobs and wealth, women and minority entrepreneurs are consistently hindered by financial and societal hurdles in the journey to grow their businesses. To make matters worse, the Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated these gender and racial disparities. Testifying before the Senate Banking Committee, Jerome Powell recently said, “Low-income households have experienced, by far, the sharpest drop in employment, while job losses of African-Americans, Hispanics, and women have been greater than that of other groups.” The Center for Responsible Lending predicts that, based on how the Covid-19 Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) is structured, some 90% of businesses owned by women and people of color will be denied financial relief.

1984 author George Orwell described political jargon as “…designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind." Similarly, venture capitalists, lenders and even large corporate purchasers of services use language which may be innocuous or even seemingly helpful to MWBEs, but 1) shows a lack of understanding of the challenges they face and 2) ultimately denies them opportunities to grow. Through our network, the Social Impact Advisory Group, we asked experts in the know about this lexicon and what changes must happen to bring minority- and women-owned business enterprises (MWBEs) equity and influence in line. Below are some common phrases.

Requiring “Track Record/Traction” is a Deal Killer

Traditionally venture capital firms sought to invest in best-in-class, underfunded yet outperforming companies. It was these “hidden gems” that performed best in the VC’s portfolios. Yet institutional investors often reject investing in MWBEs based on their lack of track record, which Michael Silton of Act One Ventures says is an excuse not to move forward. Says Silton, “If you only invest in companies with a track record, you’re investing in people who are already there, with the same networks of those that came before.”

Silton recommends that if investors are committed to investing in MWBEs, the fixation on track record should be replaced with vetting the caliber of the team to determine whether 1) it understands the market better than alternative ventures and 2) it has the diversity needed to develop talent and wealth in their unique networks.

Get an “Advisor”, Not a “Mentor”

Sharon Vosmek, CEO of Astia, an organization leveling the playing field for women entrepreneurs by providing access to capital and networks, recommends minority and women founders not use the word “mentor” when looking for an advisor to their businesses. “Mentors” rarely invest in their mentees, especially if the mentee is a woman of color. If they have a mentor, they will forever have that hierarchy of mentor/mentee.”

If you call them an advisor, they may actually invest in the company.

Never Ask, “Who Else Has Invested?”

As Warren Buffett said, “Be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful.”

In light of Buffett’s counsel, the common practice by startup investors of asking, “Who else has invested?” is a mystery. Investors truly interested in seeking best-in-class, hidden gem ventures, should be chasing those companies where no one else has invested. Vosmek says this practice of investing where only others have invested before debunks the VC belief in meritocracy, where power is determined by skill and work ethic alone. “In the lexicon of Silicon Valley, if you don’t have Sequoia looking at you, I walk.”

Vosmek believes the foundation of innovation needs to be rebuilt by asking some fundamental questions. “Places like London and New York are finally asking, ‘Why isn’t the money flowing to women and minorities?’ Silicon Valley is still asking, ‘Why are there no women and minority entrepreneurs and how can we help them with their pitch?’”

You Shouldn’t Need Sign-Off “From the Top”

Neeraja Rasmussen, CEO of Spyglaz, a machine learning platform for customer retention, was daunted. She’d heard the statistic that it took 30 meetings to secure a seed round. With the assumption that 3% of venture funding is going to women business founders, Rasmussen calculated it would take a woman 1,000 meetings to secure funding. With those odds, she decided instead to build out her client base and bootstrap her way to success.

Along the way she learned that selling her enterprise software service often required getting sign-off “from the top”, even for large corporations. She presumed that most software vendors (typically male and white) needed only mid-level manager approval. “As a woman, a person of color or minority, you’re going to run into this structural imbalance all the time.”

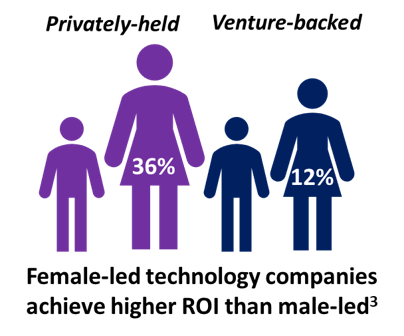

Silton agrees there is a perception that MWBEs are a riskier bet, which explains this need for minority and women founders to get senior executive approval for even the smallest of investments or contracts. He has seen this risk aversion in fundraising too. “Any time we started the conversation by saying ‘we’re going to have a higher percentage of companies founded by minorities and women,’ there was an assumption we’d make less money.”

Data that show MWBEs’ products, services and operations are no riskier and are better performing than the average may convince investors and lenders to reject their misconceptions. Still, Vosmek says, minority and women entrepreneurs need a powerful evangelist who will advocate for them when they’re not in the room. This is someone who doesn’t care about potential reputational blowback.

The economic fallout from Covid-19, which has disproportionately affected women and minorities, and protests against systemic racial discrimination are stark reminders of how far this country is from economic, social and political equality. Until the innovation economy undergoes foundational change, from within or without, to address this disparity, we need to focus on how language can make it or break it for minority- and women-founded businesses.

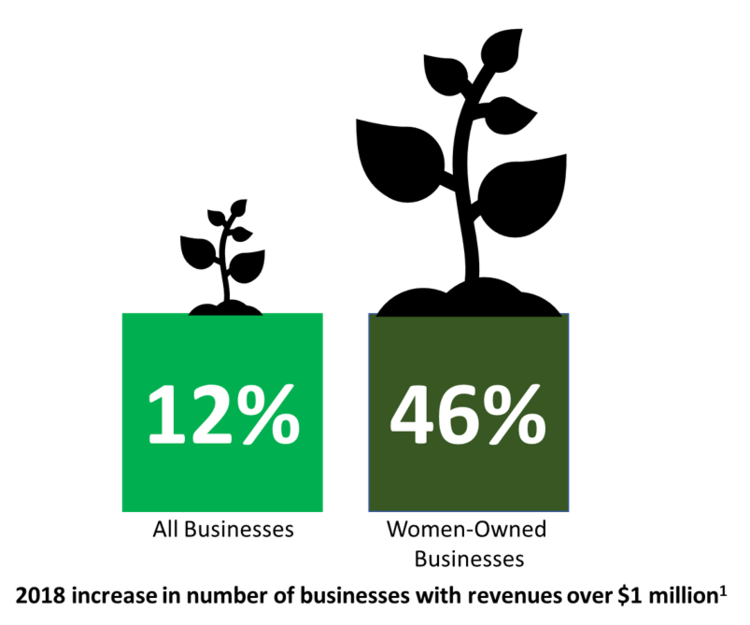

1. 2018 State of Women-Owned Businesses Report, American Express

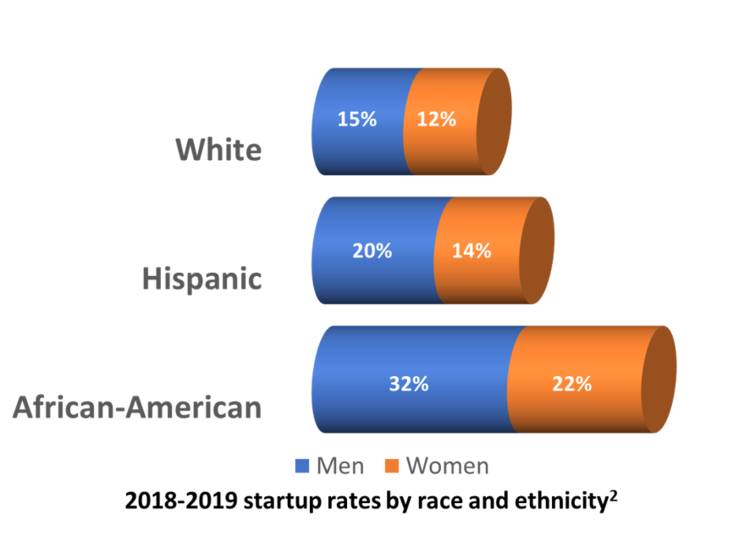

2. 2018/2019 Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, Babson College

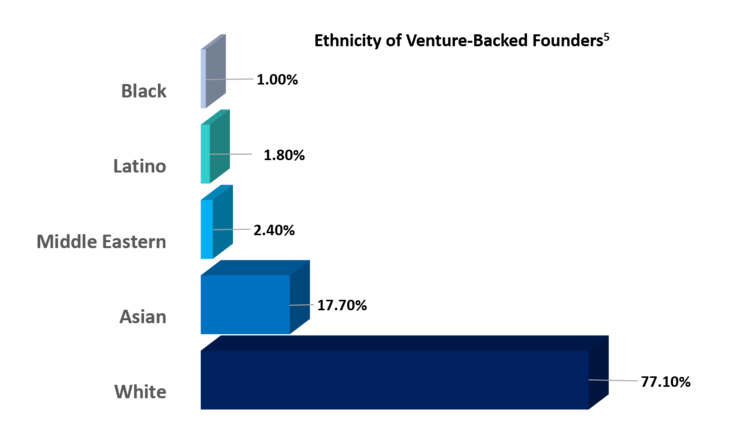

5. RateMyInvestor and DiversityVC

Related: Why We Shouldn’t Try to Predict Stock Prices