There used to be a question posed when Amazon first began eating into entire sectors – such as cloud computing, groceries, streaming video, and healthcare.

Where won’t Amazon go?

Is any sector Amazon-proof?

Today’s question is where won’t disruption go?

Is any sector disruption-proof?

Certainly, some sectors seem less exposed to disruption than others.

In the past month modular house builder Ilke Homes entered administration with the majority of the 1150 staff made redundant. This comes only weeks after insurance giant L&G ceased new production at its 475-person modular housing factory after racking up at least £174m of losses.

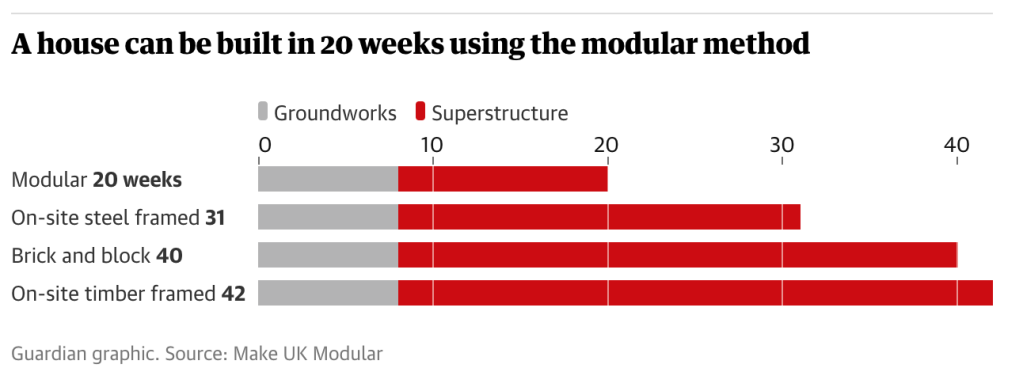

Just a few weeks earlier, the Guardian had marvelled at the ability of factories such as these to produce homes in mere weeks, disrupting the legacy bricks-and-mortar industry.

If someone told us ten years ago that the homes of the future could be built by robots, stacked on top of one another, grown in size as family needs change, have new kitchens fitted in one hour, or converted to tiny homes for our later years, we’d have bitten their hands off.

Well, the future did arrive – and we said ‘no thanks, not yet’.

So what’s gone wrong?

Most subscribers to this blog don’t work in the housing sector so I’ll spare you the various factors said to have led to the demise of these disruptors. Let’s just say that land supply, funding, over confidence, covid and, of course, Brexit have all been mentioned.

I’d suggest there’s been one underlying factor that people have avoided mentioning – a systemic unwillingness to change.

The same week that the L&G news broke I was visiting another factory and looked at a modular prototype. I won’t reveal the location or indeed the source as I’m paraphrasing what was said.

As I looked at the product, used by hospitals, schools and hotels worldwide, I asked why the housing sector in the UK was so slow to embrace it.

“It’s simple” I was told. “Your sector is the last hold-out. You throw every single barrier in the way to try and hold back the future”.

Indeed, traditional management will hold back disruptive forces at every opportunity. You don’t mess with ‘success’. In sectors such as housing, it’s entirely achievable for a very mediocre and bureaucratic manager to earn £100,000 a year just by perpetuating the system.

The social sectors like housing, health and social care have a level of protection, for the moment, that more vulnerable industries like media and entertainment, retail, financial services and telecoms simply do not.

Back in 2016, I wrote that any sector that has multiple players performing similar services is ripe for disruption. I rather optimistically (or pessimistically depending on your viewpoint) said there was no question about whether the Uber, AirBnb, Facebook and Alibaba of the public sector would emerge. It was simply a matter of when.

However, the barriers to entry in the social sector are significant and have common blocks that many stumble over:

- A monopolistic mindset. When users don’t have a choice, it dramatically removes a major incentive to innovate and improve service.

- The social sector has to be fair to everyone. This ‘fairness’ often solidifies over time into a principle of providing one-size-fits-all service. “Fair for everyone’, but exceptional for no one.

- We often lack the capabilities needed to assess and address gaps in customer experience. Those with deep analytics skills, as well as human-centered design skills, are often in short supply.

- Data is typically incomplete or sequestered in silos. Organisations often lack a full, timely picture of the overall user experience.

- The existing model keeps a LOT of people in jobs that don’t always need doing. Many of our organisations – despite the rhetoric – have policies and procedures that are profoundly anti-customer. We have built checks, balances and verifications into our process because, deep down, we don’t actually trust the motivations of the public.

So far, so depressing. The capacity for innovation and transformation is huge, but the capability for it is virtually zero.

What positives might there be? Well, in the UK it’s almost nailed on that we’ll have a change of Government next year and, although I don’t see any great vision from Labour, they will inherit an innovation super-power: an almost total absence of any money to spend. Frugality forces creativity.

Deprived of hand-outs but faced with rising demand and a broken legacy model the social sector could finally see itself robbed of its disruption-proof status.

This week UK charity foundation Lankelly Chase took the decision to abolish itself and give away its assets as it had become ‘part of the problem’. Whatever you think of their reasoning it’s a bold commitment to the future to recognise that progress is best served by you no longer being part of it.

Disrupt or be disrupted?

Or maybe, disrupt yourself or face a slow but steady decline into obsolescence.