The first step to a better investment experience talked about Understanding Market Pricing and used the story of making a pencil by Leonard E. Reed in 1958.

While simple in design, no one individual can make a pencil. The creation of a pencil is the result of a vastly complicated process wherein millions of people participate daily, creating a complex marketplace that reflects all the different prices for all the goods and services involved in making that pencil. The pencil is just one example of how markets work to set prices. Understanding how market pricing works is critical to Step 2 - Don’t Try to Outguess the Market . Trying to outguess the market by finding mispriced securities really goes against the grain in terms of understanding how markets works - or how securities are priced.

Instead of using a pencil to help us understand, let’s use a jar of jelly beans.

Perhaps you have seen the experiment where a jar of jelly beans is placed in front of a crowd, and people take turns at guessing the number of jelly beans in the jar. Amongst any given group of people, there may be some who are experienced with statistics or estimates and others who are not, yet the results are always the same. It is the collective average of all of the guesses that is closest to the actual count, versus any one individual’s guess.

What does this mean? Well, under the right conditions groups can be very intelligent. They can be smarter than any one person and smarter than the smartest person among them.

There was another experiment in 1906 that was conducted by British scientist Francis Galton.

Galton was participating in a contest at a local county fair to guess the weight of an ox before it was to be slaughtered and dressed. At the fair there were a lot of farmers and agricultural experts who should know best how much the ox weighed. Galton collected 800 entries from the participants and found a surprising and significant truth. The average of all the guesses was just one pound off the actual weight and much closer than the winning guess or the “experts.”

Related: How to Understand Market Pricing

Understanding that combined groups are smarter than any one individual is critical to understanding market pricing. If you can grasp that, it’s easy to see how the market, like a jar of jelly beans or an ox, will usually work against any single professional who thinks they can beat the market. And herein lies the problem, many traditional investment methods think this way. They try to find pricing mistakes or predict the future, which ends up being a futile and costly effort for themselves and their clients.

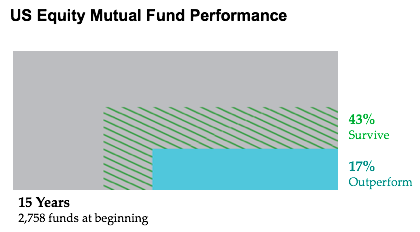

A recent academic study was conducted from 2001 to 2015 in which 2,758 active equity mutual funds were evaluated. After 15 years, only 43 percent of these funds survived, and merely 17 percent outperformed their benchmark. Likewise, another study assessed the outcome of 800 fixed income mutual funds, finding a meager 7 percent outperformed their benchmark*.

Let’s say you were lucky enough to pick one of the 17 percent from the equity segment or one of the 7 percent from the pool of fixed income funds that outperformed their benchmarks, there still remains a very significant factor to keep in mind. In fact, it is a disclosure that is so important that all firms use it: past performance is no guarantee of future performance. Just because one fund or manager has done well in the past doesn’t mean they will do well in the future.

If we want to have a successful investment experience, then we need to understand how market prices work--and then we need to know that the collective knowledge of the market is smarter than any one participant, any one money manager.

If you believe the market has it wrong, you are putting your knowledge or hunches against the combined knowledge of millions of other market participants. And that is a hunch no investor should be willing to bet on.

Related: Why You Must Ignore the Financial Media

*Beginning sample includes US equity mutual funds as of the beginning of the 15-year period ending December 31, 2015. Survivors are funds that were still in existence as of December 31, 2015. Non-survivors include funds that were either liquidated or merged. Outperformers are funds that survived and beat their respective benchmarks over the period. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.Data Source: Analysis conducted by Dimensional Fund Advisors using data on US-domiciled mutual funds obtained from the CRSP Survivor-Bias-Free US Mutual Fund Database, provided by the Center for Research in Security Prices, University of Chicago. Sample excludes index funds. Benchmark data provided by MSCI, Russell, and S&P. MSCI data © MSCI 2016, all rights reserved. Frank Russell Company is the source and owner of the trademarks, service marks, and copyrights related to the Russell Indexes. The S&P data is provided by Standard & Poor’s Index Services Group. Benchmark indices are not available for direct investment. Their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio. Mutual fund investment values will fluctuate, and shares, when redeemed, may be worth more or less than their original cost. Diversification neither assures a profit nor guarantees against a loss in a declining market.